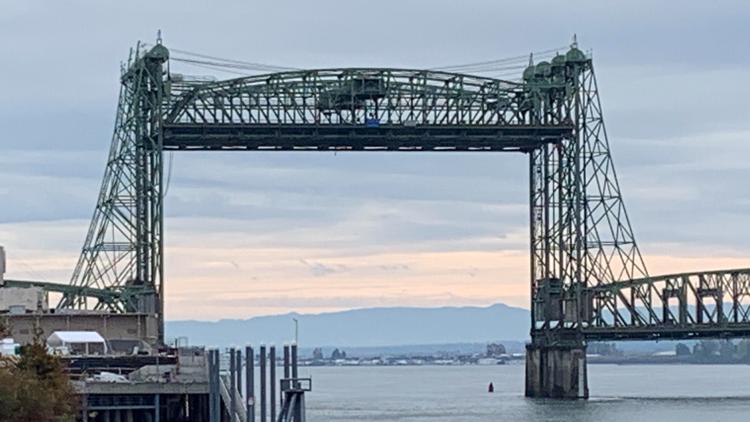

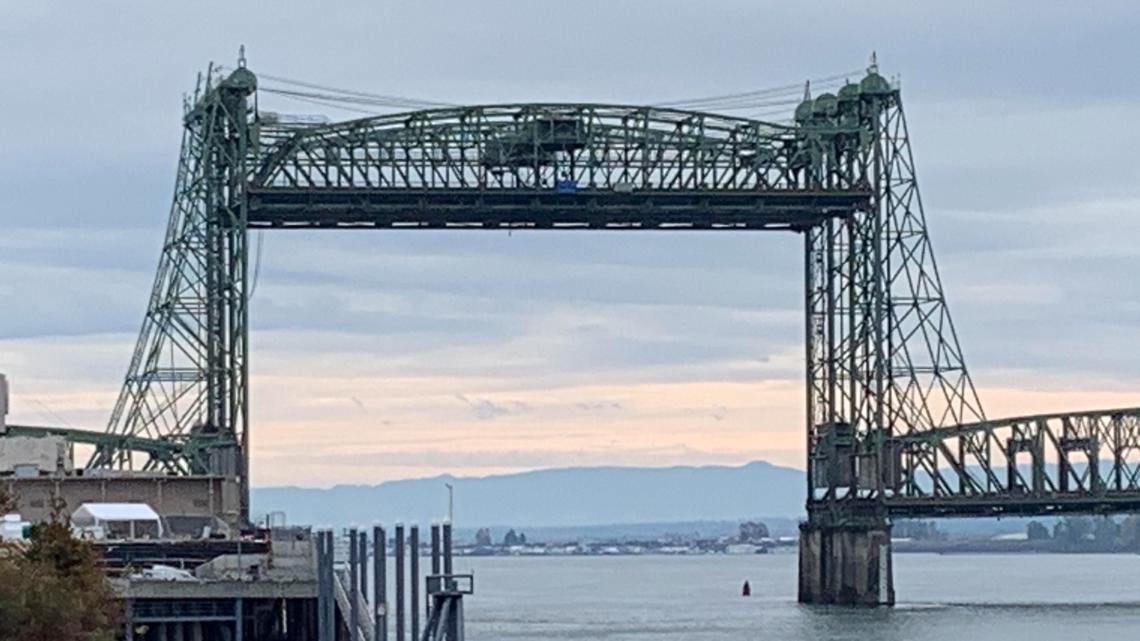

The decision settles a big lingering question: whether the new bridge will need to match the current bridge’s 178-foot clearance, which would require a drawbridge.

PORTLAND, Ore. — The U.S. Coast Guard has issued an updated decision on the amount of clearance required for a replacement Interstate Bridge, lowering the minimum height to 116 feet — a key breakthrough that will allow the Interstate Bridge Replacement (IBR) project to proceed with a “fixed span” design with no drawbridge.

U.S. Sen. Maria Cantwell broke the news in a press release Friday afternoon, saying that it had been announced by U.S. Coast Guard Commandant Adm. Kevin E. Lunday. IBR issued its own news release a short time later, saying that the Coast Guard had contacted the project team to announce its decision.

“The IBR Program now has the clarity it needs to advance and position us to build a safer, multimodal river crossing and corridor that will serve both states for generations,” Oregon Governor Tina Kotek said in a statement.

The new decision, referred to as a “Preliminary Navigation Clearance Determination” (PNCD), isn’t an actual permit for the project, but it signals that the Coast Guard will grant a formal permit for the 116-foot design when IBR applies for one — which will likely happen soon, given that the project team hopes to begin construction by September.

It’s a major victory for IBR, which has pushed for years to convince the Coast Guard to reverse an earlier decision that would’ve required the replacement to match the current twin bridges’ 178 feet of clearance — which would have necessitated building the new bridge with a drawbridge section that could lift up for large river vessels.

Debate over river clearance

Adding a drawbridge would’ve cost about $1 billion more to build, according to a recent draft cost estimate, and it would’ve meant giving up on one of the key goals of both the IBR team and many of the federal and state lawmakers backing the project: the complete elimination of the bridge lifts that routinely bring Interstate 5 to a standstill.

Washington Gov. Bob Ferguson and U.S. Rep. Marie Gluesenkamp Perez both issued statements in the past two days urging the Coast Guard to lower its clearance requirement to allow the fixed-span design, and Cantwell and Ferguson praised the decision on Friday.

“A fixed span bridge has overwhelming support from the maritime industry, businesses and community groups,” Ferguson said in a statement. “This is the right decision for our economy, and for commuters who use this bridge every day. I appreciated meeting with Coast Guard leadership to present our case in person. I look forward to continuing our progress to replace this 108-year-old bridge.”

The current twin bridges only offer about 40 feet of clearance when their lift spans are closed, and IBR argued that the vast majority of past bridge lifts have been for vessels that needed more than 40 feet but nowhere near 178 feet, and that most of them could fit under a 116-foot bridge with no issues.

The project team submitted an initial report to make that case in 2022, but the Coast Guard disagreed and issued a PNCD requiring 178 feet later that year.

IBR submitted a new report last fall that outlined a series of “mitigation agreements” that the team has reached with upriver companies that could be impacted by a fixed span’s reduced clearance — essentially paying one-time fees to those users to compensate them for the added trouble of modifying their vessels or future cargo to fit below the 116 feet limit. The specific agreements are confidential, but total out to about $140 million.

Next steps for the project

The new 116-foot determination clears one of the major remaining hurdles for the project, and it sets IBR up to clear the next one: the federal environmental review process, which has dragged on for years and can’t be finished until the project team settles on either a fixed crossing or drawbridge design.

IBR said on Friday that it will continue to work with the federal government to complete the environmental process, and that the Coast Guard’s decision will allow the project team to select a final design for the replacement bridge and pick a construction contractor.

But there’s an even larger hurdle that still remains: the project appears to be less than halfway funded. The current official cost estimate, released in late 2022, puts the cost of the project at $6 billion, and IBR’s finance plan has been built around that target, with $5.5 billion already lined up from tolls, state funding and a pair of federal grants, and one more $1 billion federal grant at the application stage.

A new cost estimate has been in the works since last year and is widely expected to be higher — although precisely how much higher remained a mystery until last week, when a pair of early draft documents from the current cost estimate process were made public through a records request.

They listed a new total cost of $13.6 billion for the project if it uses a fixed span design and $14.6 billion if it includes a drawbridge, which would leave the project with a budget gap of at least $7 billion now that the fixed span pathway is locked in.

The IBR team said in a statement that those numbers are not a new cost estimate because the documents in question are from August 2025 and essentially represent the starting point for the new cost estimate process rather than a final version — but state lawmakers overseeing the project still appear to be taking those early numbers seriously.

“Oregon needs every single penny it can muster in its general fund and directed to programs that will help Oregonians,” Oregon Rep. Thuy Tran told KGW last week. “And if this project is not viable at this time, we need to know about it so that we can redirect, we can ask for other options, right? It’s not written in stone.”

One of the project’s existing federal grants comes with a September 2026 deadline to start construction, and the project team has previously advocated for moving forward to meet that deadline using the funding on hand, even if it’s not enough to cover the full cost.

“Your hedge against inflation and escalation is getting things started,” former IBR leader Greg Johnson said in an interview ahead of his departure last month. “If you keep kicking the can down the road, you will be buried by these inflation and escalation costs.”

The upcoming legislative sessions in Oregon and Washington may shed more light on whether state lawmakers are on board with that plan — and how they might tackle the enormous budget gap that the project now faces if the new cost estimate ends up being in the same ballpark as the preliminary numbers from the August document.

To ensure diverse coverage and expert insight across a wide range of topics, our publication features contributions from multiple staff writers with varied areas of expertise.